Did you know there are uniquely Jewish foods in India? Did you even know there were Indian Jews? (I hope so, though I’m sure that at least a few of you were unaware.) Indian Jewish Food is complex, so I want to write this new primer to give you a summary of what makes up the cuisine of the Jews of India.

But before we can begin to explore Indian Jewish Food, we first need to understand, who are the Jews of India?

Who Are Indian Jews?

Historically, people have been fascinated by Indian Jews, because they have been seen as “exotic.” While that term is obviously subjective, and can even be interpreted as insulting, there is no doubt that when one finds a community of Jews (and a numerically substantial one, at that) in a place were it was unexpected, it underscores how globalized the Jewish people actually are. 2,700 years of Diasporic wanderings have brought Jews to the furthest reaches of the planet, and in many cases, Jews remained in far-flung locations that were hospitable, and had become known to them as “home.”

The Jews of India proudly highlight that there is virtually no history of antisemitism in the country, one element that greatly contributed to maintaining a Jewish life there. It also has been a cosmopolitan land, with numerous different ethnicities and religions present, again fostering a welcoming attitude. Finally, India’s importance in international trade — a significant profession of Jews from antiquity to today — brought more pockets of Jews to the subcontinent.

In broad strokes, there are three older, more sizable communities (two from antiquity and one from modern times), along with two other communities seen as “Judaizing” or “emerging” — communities that claim Jewish roots who to varying degrees are moving towards stronger integration into the global Jewish community. Whether or not their claims of Jewish heritage are historically accurate, they are clearly throwing their lot in with the Jewish nation, and working towards a stronger connection; whether that will require a formal conversion or not is a question for others to decide, not me. And even if such roots are genuine, there is no doubt that their observance of Jewish practice was not continual, resurging only in modern times. Thus, their Jewish food traditions also are less entrenched, though I will describe a bit of their food as well.

These are the primary communities:

Bene Israel — One of the ancient communities, the Bene Israel are centered in the western states of Maharashtra and Gujarat. Though they originally lived a more rural lifestyle, many community members now live in cities such as Mumbai and Ahmedabad. Smaller cities where Bene Israel live include Alibag to Mumbai’s south, and Palanpur, Vadodara, and Rajkot surronding Ahmedabad. The community believes itself to have been founded by Jews who fled Israel at the time of the Chanukkah story (2nd century BCE), and were shipwrecked on the Indian coast.

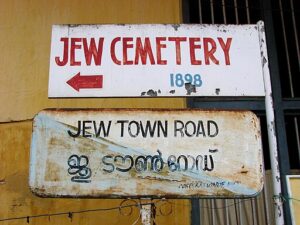

Cochin Jews — The other ancient community is located in the far south of India in the state of Kerala. The main city in which they live is Kochi, giving the community its name. They are also known as Malabar Jews, from the name of the broader Malabar region in which they live. Their origin story goes back further than that of the Bene Israel, claiming roots in the time of King Solomon, arriving as sailor traders. As with the Bene Israel story, and many other communities’ origin tales, we have no proof nor way of confirming the veracity og the story. But it certainly testifies to the community’s antiquity, at the very least.

The Cochin community was reinforced in later periods by Sephardic emigres following the Spanish Expulsion, and other Jews arriving from Yemen, nearby across the Arabian Sea. Some affiliated members of the latter group settled on the southeastern side of India in what was then known as Madras (today the city of Chennai). These additions to the Cochin Jewish community became known as Paradesi (“foreign,” as opposed to desi, “local”) Jews, and at times were integrated with the other Cochin Jews, and at other times at odds with them.

Baghdadi Jews — Starting in the late 1700s, and more so in the 1800s, India saw an influx of Jews from the broad Middle East region. Many came from Iraq, giving the community its moniker, but the “Baghdadi Jews” of India actually came from many places. Some from Syria and others from Persia, among other places. Arriving during the colonial era, these Arabic-speaking Jews quickly westernized, shedding their Middle-Eastern garb for European styles, and integrating culturally with the English occupiers. They were heavily involved in international trade, and formed the base of a network of communities throughout southeast Asia. When they first arrived, they lived in the same area as the Bene Israel Jews, and actually received early assistance from them. Later, however, tensions grew between the two groups, and while some Baghdadis remained in Mumbai, the bulk became centered in the northeastern port city of Calcutta, West Bengal.

Bnei Menashe — One of the two more recent communities on this list, the Bnei Menashe grew out of tribal communities in the far northeastern states of Manipur and Mizoram (east of Bangladesh). The groups name grows out of their tradition of descent from one of the so-called “Lost Tribes of Israel,” Menashe. Historically, the community had been proselytized by 19th-century Christian missionaries, and during the 20th century, a leader brought many community members to reject that religion in favor of the Judaism he saw as their heritage. Their main home towns include Imphal and Churachandpur in Manipur, and Aizawl in Mizoram.

Bene Ephraim — The smallest of the communities I am covering here, the Bene Ephraim claim roots in another of the lost tribes, Ephraim (the brother of Menashe and other son of Joseph). This group, like the Bnei Menashe, claim ancient Jewish roots, but only began practicing a form of Judaism during the 20th century, starting in the 1980s. The community is centered in Andhra Pradesh state, north up the coast from Chennai. Centers are in Vijayawada and Machilipatnam.

So What do They Eat?

There are, first of all, a few commonalities between the foods of the Indian Jewish communities. One of the telltale signs that ties these different groups’ cuisines together is the use of coconut milk in their curries. Many Indian curry dishes are made using dairy products such as ghee (clarified butter) and/or yogurt. But to avoid mixing dairy and meat (forbidden by traditional Jewish laws of kashrut), Indian Jews typically replace the dairy thickener with coconut milk (and use oil instead of ghee).

Additionally, kosher meat is not always easy to find in India. Therefore, while there certainly were always meat dishes within the menus of Indian Jews, fish is a more commonly consumed protein. They were much more readily available due to the locations of the communities along coastlines and interior waterways. And fish, according to Jewish law, do not need specialized technical slaughter the way poultry and quadrapeds do. Also, since kosher poultry is more easily obtainable, chicken is a more common element in Indian Jewish dishes than is beef or lamb. Interestingly, with the difficulty in getting kosher beef or lamb, one would expect that when an animal is slaughtered, it would not all be eaten at once. Yet I have not come across many examples of preserved meat (e.g. salted, smoked, dried, etc.) cropping up in Indian Jewish cuisine, as one does in the foods of some other cultures (such as that of Kurdish Jewry). Perhaps it was simply more common, historically (before modern refrigeration and freezing technologies), to share a slaughtered animal among a larger group of people, thus minimizing the need for preservation.

Spices, as with all cuisines in India, are widely used, though as we’ll see, not identically in each community. Common to all are such ingredients as garlic, ginger, green and red chillies, cardamom, cinnamon, and cumin.

Bene Israel Jewish cuisine features a wide array of fruits and nuts, including raisins, dates, bananas, guavas, cashews, pistachios, and almonds. A few ingredients that are specific to this community, as opposed to the other Jews in India, include cocum petals, powdered sesame, flaked rice (poha), and chironji seeds.

Perhaps the most famous Bene Israel dish is used in a ceremony unique to this community, known as Malida. The Bene Israel community bears a special affinity for the ancient Jewish prophet Elijah, and many lifecycle events are marked with giving praise and thanks to him. The classic malida platter includes poha, grated coconut, raisins, almonds and various spices.

Due to their historical involvement in the spice trade, and the region in which they live, the Cochin community’s food features an even wider array of commonly used spices. A few examples include mustard seeds, tamarind, and curry leaves. While fruits are still consumed, there is a smaller variety with more vegetables entering the cuisine. Carrots, celery, cucumbers and cabbage all fall into this category.

The Baghdadi community’s food connects most strongly to its country of origin. Many of the dishes eaten by Baghdadi Jews are straight-up Iraqi or Middle Eastern foods, but with an Indian twist. For example, a popular version of their hamin Shabbat stew combines rice and chicken, the way that an Iraqi t’bit does. In fact, some Baghdadi Jews stuffed their chickens for Shabbat, making an actual t’bit. The difference, however, is in the spicing. While in Iraq, a baharat blend was common, among Baghdadi Indians we find the use of ginger; whole cardamom pods, cinnamon sticks, and cloves (rather than ground); and garam masala. I have also come across examples that freshened up the hamin with a cilantro-ginger-garlic chutney (as pictured at the top of this post).

The Bnei Menashe cuisine is simpler, with fewer ingredients and less spicing. The region they live in is fairly mountainous and has a temperate climate. Boiled spiced leafy greens (known as Bai) and fried foods (called Kan) are common dishes for the region, among Jews and non-Jews alike. A few special ingredients for this community are mushrooms, betel nuts, parkia beans, colocasia, and soy sauce.

Finally, Bene Ephraim food may most reflect its region. Situated in a tropical region of India, they consume many tropical fruits and vegetables, such as papaya, bamboo shoots, elephant apple (not actually an apple), and bottle gourd. Nigella seeds, okra, and peanuts are other common ingredients.

Sources to Explore Further

This was only a very brief summary of the widely-varied Indian Jewish Food. But if you’d like to explore more, there are many further resources available to you. It is interesting how some Jewish communities have had very few cookbooks profiling their dishes (e.g. the Jews of Greece, where there is really only one that I know of), while other communities have many (such as Italian Jewry’s cuisine). Luckily, India falls into the latter category. Here are a few books you can check out:

- Spice & Kosher: Exotic Cuisine of the Cochin Jews – Dr. Essie Sassoon, Bala Menon, Kenny Salem (2013)

- Indian-Jewish Cooking – Mavis Hyman (1992)

- Bene Appétit: The Cuisine of Indian Jews – Esther David (2021)

- The Varied Kitchens of India – Copeland Marks (1986)

- Bene-Israel Cook-Book – The Jewish Religious Union Sisterhood, Bombay (1986)

Additionally, there are many sources online, that you can find via a search engine.

Enjoy the exploration!

Share This Post with Someone Who’d Love It!