Bourekas are one of those foods that are uber-popular here in Israel, and becoming better-known around the world. But many people don’t know their country of origin — Turkey — and even fewer know that they were actually invented by Turkish Jews. Bourekas (or burekas or borekas or however you choose to spell them) are actually a true Jewish Food, as I mentioned in this post, and not only because we invented them. I don’t believe that is enough of a reason to classify something as a Jewish Food, as I wrote there.

Bourekas, however, are a Jewish Food because in addition to being invented by Jews, they also reflect Jewish History.

What Are Bourekas

Before I get into the history, I need to describe bourekas, for those who may be unfamiliar.

In broad strokes, Bourekas are pastry turnovers, typically around 3 inches in diameter, filled with a variety of usually savory stuffings, such as potato, cheese, spinach or mushrooms. They are crispy, sometimes are topped with seeds of some kind, can be eaten warm or at room temperature, and are one of the more delicious and tempting street foods in Israel.

Bourekas also make up one part of the classic trio of Sephardic Jewish pastries, affectionately referred to as “The Three B’s” — bourekas, boyos and bulemas. (I considered including them all, along with the ways to differentiate between them, in this post, but realized it would be way too long. Look forward to a separate post or two on that topic, while I stick with bourekas alone in this one.)

Some of the classic fillings that appear to have dropped from popularity (at least as a mainstream baked good in Israel, though probably remaining in the homes of Sephardic Jews around the world) include pumpkin or winter squash (particularly for Rosh Hashana and Sukkot) and eggplant. Meat-filled bourekas are not uncommon on Friday nights, but typically are homemade and not purchased in commercial bakeries.

So What Makes Bourekas Jewish?

As Gil Marks writes in his Encyclopedia entry on bourekas, like most Jewish Foods, they are “a synthesis of cultures and styles; over the course of history, they have been transformed and transferred, on their way to becoming a ubiquitous treat in modern Israel.”(1)Encyclopedia of Jewish Food, Gil Marks

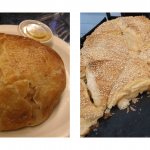

Although there were Jews living in Turkey since ancient times, the majority of the Turkish Jewish population descend from the Sephardic Jews of Spain who moved to the Ottoman Empire after they were expelled from Spain in 1492. When the Catholics kicked the Jews out, the Muslim Turks welcomed them in. And they kept cooking Spanish foods. Can you think of a Spanish food that kind of resembles a boureka? (In particular, look at the top right boureka in the main picture for this post — the most “genuine” boureka of the lot.) A handheld pastry turnover with stuffing inside?

Empanadas! The empanada comes from Spain and subsequently spread to Latin America (where it is very popular) and other areas with Spanish heritage. They often have meat and vegetable fillings inside. Now here’s where things get interesting.

The Spanish Jews kept cooking empanadas in Turkey. But right around the same time that they arrived in the Ottoman Empire, there was another food that was becoming all the rage there. Called borek, it was a modification of a filled hand-pie (called burqa) that the Turkic people knew from their origins in central Asia. One of the newest Turkish culinary inventions at the time was a paper-thin dough called yufka, very similar to what we know today as filo/phyllo pastry. (Yufka is hand rolled and slightly thicker than filo, which is stretched.) Yufka replaced the previous dough of the burqa.

While the Sephardic Jews were fairly welcome and comfortable among the Ottomans, they still kept somewhat apart without fully integrating. And so they were slow to adopt Turkish foods. Still, after approximately 150-200 years, they basically looked at the borek, saw that they had wonderful fillings, and decided to stick borek fillings into their empanadas. And thus, the boureka was born. This way, they got a finger-food version of the borek, and a non-meat version of their empanadas (allowing them to eat it with dairy meals as well).

Two main things differentiate a borek from a boureka:

- Size: Borek are significantly larger, often 9-12 inches in size. Sometimes they will be cut into pieces, sliced lengthwise for sauces to be added

- Dough: Borek typically use yufka; bourekas an oily short dough, similar to empanadas

These days there may be some fillings common in a boureka that aren’t found in borek, or vice versa. But that’s a newer development.

Names Can be Confusing

I just wrote that bourekas are typically made with a dough that is similar to that of an empanada, and many of you may be saying, “No they aren’t! They’re made with filo or puff pastry.” But that is part of why I also wrote above that the one in the top right of the plate is the most “genuine.”

For example, Claudia Roden(3)The Book of Jewish Food, Claudia Roden points out that in Italy these are known as burriche, with different standard fillings. The name Borekitas is used for a specific type of boureka that is always filled with cheese and often has cheese or yogurt in the dough,(4)The Jewish Kitchen: Recipes and Stories from Around the World, Clarissa Hyman though pastries of a similar style are known in Izmir as handrajos.(5)Sephardic Flavors, Goldstein Meanwhile, Bourekakia is a Greek name for one that is filled with meat.(6)The Cookbook of the Jews of Greece, Nicholas Stavroulakis

True purists only use the term boureka to describe the small hand-pies with the empanada-esque pastry. Puff pastry is a later invention, and thus also a more modern innovation for this dish, mainly for convenience, and thus not a traditional pastry. If filo-type dough is used (as in the triangular type at the bottom of the main picture), traditionalists differentiate it by calling it fila or filica. Others use some variation of ojaldre, holjadre, rojaldre or the like.

And if all that wasn’t confusing enough, here in Israel the single term boureka is all-encompassing, describing all types of these handpies, and even the larger Turkish borek types (referred to here simply as “Turkish Bourekas”). And the “s” that makes it into a plural isn’t understood by most Israelis, so bourekas became a singular word, and the plural is the Hebrew bourekasim. (Israelis make the same mistake with other words as well, so that you can order “one brownies,” for example.)

The Israeli Boureka Code

I may have confused you with all of that, so now I want to help ease that confusion, at least for those of you who come to visit in Israel and want to buy bourekas without looking like a yokel.

As you can see from the main photo, there are many types of bourekas in Israel, and they come in a wide variety of shapes and with various toppings. (I bought all of those from a single store in Jerusalem’s Machane Yehuda Market.) So how do you know what’s inside without badgering the store’s employees?

My friends, there is a code! It isn’t a secret (though if you look online, people who write about it don’t always get it right). But those different shapes and toppings are actually what tells you the filling. Now since I don’t like spinach, I didn’t buy any of those, and a few of the ones in the picture are unique or new-fangled ones from this store. And yes, occasionally a store breaks the code, so it isn’t 100% foolproof. But still it should work most of the time.

Follow along with the main photo, and learn! In the center, is the easiest to identify. That’s a newer type of boureka with pizza sauce and cheese. It is round, flat and has cheese on top. (In this case, they had a regular pizza one which I didn’t eat due to the olives, which I also don’t like. This one with the black nigella seeds on the side is to mark it as pizza with kashkaval cheese instead.) Below that, at the very bottom, the filo triangle with sesame seeds has cheese filling. This is one of the most standardized ones you’ll find nearly everywhere. Above it to the right, the more puffy and thick triangle with poppy seeds contains mushrooms. And above that, the classic half-moon shape with short pastry dough has a saltier cheese filling.

The other three on the plate don’t follow the “rules” closely, and I’m even going to ignore the two on the left (both cheese variations that are non-standardized). The one on the top that is the same shape as the mushroom, but has sesame seeds on it, in this case is potato-filled. This is abnormal — almost always, potato bourekas are rectangular in shape, sometimes with sesame seeds, sometimes not. And spinach (as I said, not pictured) is typically in a small spiral or ring shaped pastry.

So there you have it! All you ever wanted to know about bourekas (and the many related pastries), as well as its little-known Jewish history. Bottom line, if we didn’t move from Spain to Turkey, there wouldn’t be a boureka in the world. And as any of you who have had them will agree, that would be very sad.

Leave it to me to find a culinary silver-lining to the Spanish Expulsion!

Footnotes

| ↑1 | Encyclopedia of Jewish Food, Gil Marks |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Sephardic Flavors: Jewish Cooking of the Mediterranean, Joyce Goldstein |

| ↑3 | The Book of Jewish Food, Claudia Roden |

| ↑4 | The Jewish Kitchen: Recipes and Stories from Around the World, Clarissa Hyman |

| ↑5 | Sephardic Flavors, Goldstein |

| ↑6 | The Cookbook of the Jews of Greece, Nicholas Stavroulakis |

Betty Resnick (Benveniste)

Thank you for this wonderful article!

My Sephardic family loves borekas. My parents and 4 grandparents are all from Turkey – Istanbul and Izmir. For us borekas are always made with pastry dough, and boyos with filo. My Nana would bake traysful of them, together with fritatta, and bring them to our house in the morning, hot from the oven. We devoured them.

My fritatta and borekas are good, but don’t measure up to my Nana’s. I have been confused by all the different variations and names for borekas throughout my travels, including Israel, so thanks for clarifying.

Betty Resnick

FunJoel

Thanks for this, Betty! Firstly, I’m glad I could help!

Secondly, I will talk more about it in my post(s) about bulemas and boyos, but based on your comment, I’m curious…

Does your family have any connection to Rhodes? Because so far, I have only found Rhodeslis that refer to a filo-based pastry as boyos. For most others, boyos is more of a bread base.

Betty Resnick (Benveniste)

I’m not aware of any family connection to Rhodes, but often heard my parents refer to Rhodeslis.

My mother’s birth surname was Siva; she was adopted by her maternal aunt (Behar, married name Benezra) when her mother died from the 1918 flu. Have never seen Siva in Sephardic lists of names. Have you?

FunJoel

Thanks for your reply, Betty. It is interesting to think about where that shift occurred (referring to a filo pastry as boyos, rather than a bread-dough one). I was only asking since it was the only ones I’d found so far. But this might simply add to the question. Other than being made with filo, what else differentiated the boyo as a pastry for you? Was there a specific shape? Filling?

Regarding the Siva name, I can’t recall ever seeing it. But that is also not an area I am well-versed in. So it isn’t surprising that I haven’t! 🙂

Betty Resnick

Hello FunJoel,

Regarding boyos made with filo, I believe my grandmother made her own dough. Not sure if filo was available to purchase back then. I have deep regrets that as teenager and young adult I didn’t pay much attention to my Sephardic traditions, except that I loved the food and still do.

We had 2 types of boyos. The potato and cheese filled ones were square shaped and the spinach and cheese were round and coiled into a spiral shape, so we could select the filling based on shape. Both were flaky and crisp. I recall that the cheese boyos, were topped with grated cheese, but not the spinach ones.

The borekas were turnover shaped and filled with either cheese and potato or a ground meat mixture, and topped with an egg wash (made them shiny) and sesame seeds.

I don’t recall anything she made called bulemas. She and my mother made bumuelos – small potato and egg “balls” deep fried or sweet doughnut-like ones with honey.

And then there’s travados…but that’s another story.

Fascinating discussion!

FunJoel

So, from your description, it sounds like your spinach and cheese ones are what others refer to as bulemas, or rodanchas in Greece. They are invariably spiral, and often described as snails or roses (the meaning of rodanchas).

But more on that when I write my post about boyos and bulemas!

And travados is something I’ve never heard of! Feel free to email me info on that. 🙂

Jews Were the Original Culinary Movers and Shakers (Literally) - The Taste of Jewish Culture

[…] my post about Bourekas, I touched on some of the culinary results of the Jewish forced migration following the Spanish […]

Börek – Wikipedia – Enzyklopädie

[…] (04.06.2020). “Die unbekannte jüdische Geschichte von Bourekas”. Der Geschmack der jüdischen Kultur. Abgerufen […]

The Savory Israeli Pastry You Should Know - Michelleinthehouse.com

[…] Toppings can also hint at what’s inside. Many bourekas are topped with sesame seeds, but other toppings like nigella seeds or a combination of both are found too. Knowing what toppings represent which filling keeps hungry shoppers from pestering the server behind the counter, inquiring what’s inside (via Taste of Jew). […]