The question above, or the similar one that replaces “bagel” with “pastrami,” “knish” or something else of the sort, is one of the most frequent I receive, both as an American-Israeli food researcher, and as a tour guide specializining in culinary tours. When I received some form of this question on a recent tour in Machane Yehuda Market, I answered as best as I could in the short time I had allotted, but realized this was a topic I should try to address in greater detail, here on the blog.

Looking back at some earlier, related posts, I realized that a few of the points I want to make, I already wrote about in my post about the history of the American Jewish deli. But I do have one or two new points I want to add here. So I will summarize and clarify the points I previously made and then add to them.

You’re a Minority

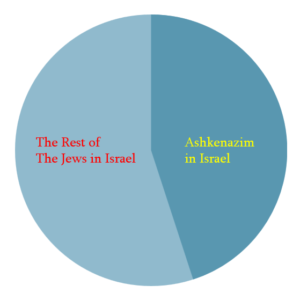

The first thing to understand about food in Israel is that it very much reflects the population here. Yes, Israel’s population is approximately 3/4 Jewish, and yes, in Israel the term ochel yehudi (“Jewish food”) most frequently references Old School Ashkenazi cooking. But still, the millions of Jews living here are not primarily of Ashkenazic descent. In Israel, Ashkenazim make up under 50% of the Jewish population; we’re a minority here!

This can certainly seem shocking to Americans, or is at least frequently overlooked by them, because in the US, somewhere in the neighborhood of 95% of the country’s Jews are Ashkenazi. This has created a so-called “Ashkenormative” mindset, where Ashkenazi Jewish culture is often perceived as synonymous with Jewish culture.

Bottom line, though? Ashkenazim are the minority in Israel, so we need to get used to the fact that our foods will not be as prevalent here as they are in countries where Ashkenazi Jews are the numerically dominant culture. And even if you want to argue that we are still a plurality (less than a majority, but still the largest single minority group), that explains why plenty of Ashkenazi food does exist in our cuisine and is not impossible to find. You just need to look a bit harder, and/or go to areas where Ashkenazi Jews far outnumber Sephardi, Mizrachi, and other Jews (no, Jews don’t all fit into two or three neat categories/boxes).

You’re Not Talking About Ashkenazic Food

More accurately, you’re not talking about traditional European Ashkenazic foods. The foods that are thought of as Ashkenazic classics today are often quite different from those that were eaten in Eastern Europe, Germany, or Hungary. They were largely altered in America, as the result of greater wealth, abundance of food, etc.

Similar things occurred in America with other classic Jewish foods from Europe. Bagels grew exponentially in size. Foods from widely distant parts of the Jewish European world ended up served side-by-side in American Jewish delis. And foods that were generally eaten by both Jews and non-Jews in Europe, such as rye bread, became associated with Jews in America because we were the ones who introduced them to the States, or most widely consumed them (hence, so-called “Jewish rye bread”).

So if what is thought of by many as “Ashkenazic food” is actually “American Jewish food,” that also explains, in part, why it isn’t super popular here. The foods that we most frequently find in Israel were brought here by one group of immigrant Jews or another. But there has never been a truly significant aliyah from America. Sure, there are many who have come (myself and my family among them), but we are still a drop in the bucket of the Israeli population, and a tiny percentage of American Jewry. This is a bit paradoxical when you think of Israel’s obsession with American culture. There certainly has been an influence of American foods in Israel. But when you look more closely, that connection fits in more with the general cultural dominance America has around the world. The American foods you see most in Israel are the same that you see elsewhere around the world: McDonald’s, Coca-Cola, and American style pizza (very different from its Italian forbear).

Yes, there are still many Jews of Ashkenazic descent in Israel. But they largely got here straight from Europe, or other interim destinations, not via the United States. So while we might expect to find (and certainly can) various Ashkenazi foods to consume in Israel, they are not going to be the American versions of those foods. We’ll see American influence and Ashkenazi influence, but significantly less American Ashkenazi influence.

Cultural Shifts in Israel

Though it was never the only food available here, Ashkenazi foods were significantly more common in the early decades of the State’s existence. One easy way to see this is via the cookbooks that were written in or about Israel over the years, and tracing the changes in the recipes. Early on, you see a high percentage of old-fashioned European-Ashkenazi recipes, while there are also many dishes from around the Jewish Diaspora. Good examples include Molly Lyons Bar-David’s 1964 The Israeli Cook Book, or Lilian Cornfeld’s numerous early works. Once you move into more contemporary times, Ashkenazi cuisine takes a back seat in Israeli cookbooks. Among those that focus on a specific regional cuisine, there are relatively few that focus specifically on Ashkenazi foods (a notable example would be Shmil Holland’s Schmaltz), with plenty more from the many other Jewish ethnicities. Beyond that, when looking at those cookbooks that showcase the broader Israeli cuisine (e.g Janna Gur’s 2007 The Book of New Israeli Food), the percentage of Ashkenazi dishes has dropped significantly.

This shift parallels changes in Israeli society overall. Since many of the founding fathers (and mothers) of the State of Israel were Jews from Europe, Ashkenazi culture enjoyed dominance in the early decades of the country’s existence. This was seen in government leadership, salaries, and also food. A piece of culinary evidence is that many of the popular restaurants that today still sell ochel yehudi are ones that have been in existence for 50 years or more; they are remnants of this past Israel in which Ashkenazi culture dominated. This remained the case despite rapidly increasing numbers of non-Ashkenazi immigrants from across North Africa, the Middle East, and southern Europe. Ashkenazi hegemony attempted to force non-Ashkenazi immigrants to become more Ashkenazi under the guise of “becoming Israeli.” They wanted all Israelis to be unified and similar… so long as they were unified and similar in a way that resembled themselves.

The cultural scales began to tip in the 1970s, with these other population segments flexing their muscles and reclaiming their own heritage. On the food level, we started to see more eateries that focused on Mizrachi cuisines. We also increased awareness and celebration of the Mimouna holiday. And the Israeli army also changed its menus to more accurately reflect the foods with which most soldiers were familiar. Many of these changes have been explored deeply by Israeli food scholars; I recommend the book Jews and Their Foodways, and in particular (on this topic) the articles in it by Ofra Tene (“The New Immigrant Must Not Only Learn, He Must Also Forget”), Liora Gvion (“Two Narratives of Israeli Food: ‘Jewish’ versus ‘Ethnic'”), and secondarily those of Orit Rozin, Esther Meir-Glitzenstein, and Nir Avieli.

So, to summarize. Ashkenazi Jews are a minority of Israeli Jewish culture, and over the past 40 years or so, Israeli cuisine has caught up with the population itself and reflects the diversity one finds here. And even when one does find Ashkenazi food in this country, it still might differ significantly from the foods most popular iterations in the United States.

Sharing is Caring! Pass This Post Along Via Your Social Channels!

Israel P.

I found it difficult to find blintzes at Rami Levi in Jerusalem before Shavuot. Lots of Mizrahi things, but not blintzes.

What Is Kitniyot?

[…] of the exiles. Jews from all over the globe have moved to Israel and built new lives there. And as I’ve written previously, Ashkenazi Jews are a minority in […]

Tom Dubberke

Some of the American Jewish foods arising out of Eastern European Jewish foods may not play as well in Israel compared to New York because of climate. During cold winters people like heavy, fatty foods that help keep you feeling warm and well stoked. If you don’t grow up with it, it may not be as appealing where the winters aren’t so cold.