Some of you may recall that one of the first books I reviewed for this website, even before I officially innaugurated the “From the Jewish Food Bookshelf” series, was Haroset by Susan Weingarten. I also had the pleasure of interviewing her on that topic for Episode 4 of my podcast. So when her new book was released, I was eager to read it, and review it here.

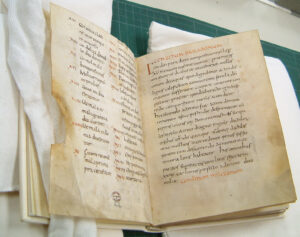

Though I’ve shortened the title in the heading of this post, her wonderful new work is called Ancient Jewish Food in its Geographical and Cultural Contexts: What’s Cooking in the Talmuds? A few of the details in that title highlight what makes this work unique, and valuable. The Talmud is the primary source material for this book, but as I’ll explain a drop more soon, you’ll notice that the last word in the title is plural — Talmuds. That is because there are actually two separate multi-volume works called by that name, one that was compiled in the land of Israel, and one in Mesopotamia. Weingarten explores food in both works.

The fact that they were compiled in different areas also explains the “geographical” context mentioned in the title. The people of each region did share some similar eating habits, but what is perhaps more notable is when they differed. Weingarten looks at this as well.

Most significant, however, is the “cultural” context of the food. The two regions in which these Talmuds were compiled were not just geographically separated. The land of Israel was under Roman control, while Mesopotamia was not, and was more influenced by Persian and other local habits.

Contextual Sources, and Relevance

One of the key impetuses for writing this book was a realization that Weingarten had. We have a number of ancient sources that talk about food, from early cookbook manuscripts to other related documents. But the Talmuds differ from those sources. The majority of texts focus on what wealthy and/or important people ate, while the Talmuds relate to the common person and his or her eating habits. The Talmuds may not offer recipes, per se, but they do provide many wonderful bits of information when we glean the food facts out of the texts in which they are mentioned. As she writes early on:

The rabbis of the Talmuds wished to regulate food consumption by Jews in line with their own conceptions of halakhah, religious regulations. They were, therefore, more interested in ordinary people and everyday foods, rather than the luxury foods of the rich which were the concerns of the non-Jewish literate upper classes. Thus they give us a different perspective on ancient food, which complements the information from outside sources.

The two regions’ foods did not only differ based on their cultural contexts. Weingarten also explores the dietary differences based on climate and geography. Different foods were available in each region.

Ancient Jewish Food looks at ingredients, dishes, and even cooking methods (and who did the cooking). It explores both the foods of the indigent and the better off, as well as both the important foods (both in their status as staples, and in the honor they receive) and the more common.

That being said, Weingarten admits that her text cannot be comprehensive. The sheer length of the two Talmuds would mean that a fully comprehensive look at food in them would be at least five times as long as this book is. She has done a good job, however, of selecting foods and topics that illustrate important aspects of the period’s Jewish foods.

And What About Those Foods?

In Chapter 3, Weingarten points out that bread was the staple food for everyone at that time. But what kind of bread differed by class. There was bread made from barley and from wheat, for example, for poor and rich respectively.

But with such a relatively bland substance as the main source of calories consumed, there was a need to spice things up a bit. Both cultures used special fermented foods that added a strong, pungent taste, as Weingarten highlights in Chapter 5. In the west, as with the rest of the Greco-Roman world, they fermented fish into various types of sauces, such as garum, liquamen, and the like. These largely varied from each other in quality. Meanwhile, over in Mesopotamia, they instead used a grain-based paste, known in the Babylonian Talmud as kutach. Weingarten finds parallels for these foods in the surrounding literature, and even entertainingly tells of a failed experiment at recreating garum (in Chapter 9: Reconstructing Recipes).

In looking at proteins, Weingarten explores the question of how common or uncommon (red) meat was as a food. Numerous references to meat are scattered throughout the Talmuds, but a key question, she points out, is whether they are descriptive, or aspirational fantasies. At first she concludes that people then probably ate more meat than we might expect, but it still was unlikely to have been a very common foodstuff. Still, she adds that archaeology has recently contributed a lot to the debate, and scholars have still not been able to resolve this issue. Numerous references to eggs exist throughout the Talmuds, but we almost never hear of chickens being eaten. So while they presumably would have been consumed when they got old, it seems that the birds were primarily raised for their eggs, rather than their meat. Fish, meanwhile, was second only to meat in prestige in Israel, with the added benefit of their ability to feed poor people. Small fish exist, but no real small animals (not counting poultry).

In terms of cooking methods, Weingarten looks at numerous egg preparations in Chapter 4. The midrash, in fact, claims there were two-hundreds ways to prepare an egg (though that description is clearly meant to idealize the times of the Temple, rather than to be a literal description). Along the way, we also learn about some professional cooks. While some baking was done at home by the housewife, there was also a professional male baker outside of the home, known as a nachtom. Additionally, a magiros was a chef for meats in the land of Israel.

Some Interesting Details

Scattered throughout the book, Weingarten uses her fast-paced writing to move us through the material pleasantly, rather than getting bogged down in too many details. This is academic writing, but remains accessible. Few discussion points are belabored. So we get to encounter many entertaining and interesting details along the way.

I particularly enjoyed encountering many familiar foods from today in these ancient sources, reminding us about the type of continuity we encounter when examining food history. Among the foods she highlights that are still eaten today are early versions of merguez sausage, huevos haminados (slow-cooked hard-boiled eggs), and even a reference to a honey-mustard combination! (I’d love to know if that is the earliest reference to this famed blend, or whether there are earlier sources for it.)

One of my pet interests within the field of Jewish Food history is the throughlines we find in Jewish cuisine scattered around the world. Despite the many individual dishes that Jews eat in each location, certain ingredients and flavors remain popular among Jews everywhere. A few crop up in this book as well. For example, both Talmuds hold garlic in extremely high esteem, as have Jews everywhere throughtout the ages. While it is also popular among the Arab cuisine that Weingarten compares to the Babylonian Talmudic sources, she points out that by contrast, Greco-Roman cuisine tended to avoid garlic.

An example of an ingredient that may not be as widely popular, but remains common for many Jews around the world is dill. It too was very popular in Talmudic times.

As a final word, I must point out that this book was published by an academic press, and is priced as such. It is aimed at institutional buyers, rather than casual consumers. But for anyone interested in the subject, it is an excellent work, that would be well worth the effort of locating it at a local library, or splurging to treat yourself if you’re particularly interested!